1 Introduction

1.1 Problem

1.2 Tyche and The Norns Dialog

1.3 Archetypal Example

Bullet payments?

1.4 Why the Problem Is Hard

Corporate finance is near unanimous in recommending net present value (NPV) as a way to evaluate investment opportunities, Brealey and Myers (1981). To decide whether to invest in a project, estimate its cash flows and then discount them at an appropriate risk-adjusted target rate of return (opportunity cost of capital) to calculate their NPV. The project should be undertaken if the NPV is positive. The project can be regarded as borrowing from and repaying a capital provider (investor) at their hurdle rate. The fact the NPV is positive translates into net value being transferred to the investor, explaining its decision rule. The analysis usually assumes all-equity financing and separately evalutes the cost or benefit of alternative financing schemes, such as the tax benefits of using debt. Writing an insurance policy is an investment opportunity that can be evaluated using NPV and a new finance MBA would be surprised that insurance companies make applying net present value to investment decisions so complicated. This section explains why insurers face several genuine difficulties using the standard NPV technique, difficulties that become the main themes of the monograph.

1.4.1 Textbook NPV analysis

Before considering insurance, it is important to understand the basis of NPV’s preeminent position within capital budgeting. It is founded on five desirable characteristics.

- It is additive: the value of a portfolio of projects is the sum of their individual values.

- It is denominated in currency units that are universally comparable and directly interpretable.

- It is based on objective cash flows, not accounting values depending on a particular standard.

- It gives more weight to earlier cash flows due to the time value of money, reflecting the greater value of money received sooner compared to later..

- It incorporates project risk through an appropriate cost of capital.

In part, these characteristics reflect the assumptions of a textbook capital budgeting problem: capital is spent not allocated, cash flow are negative then positive, projects are standalone, and value is additive.

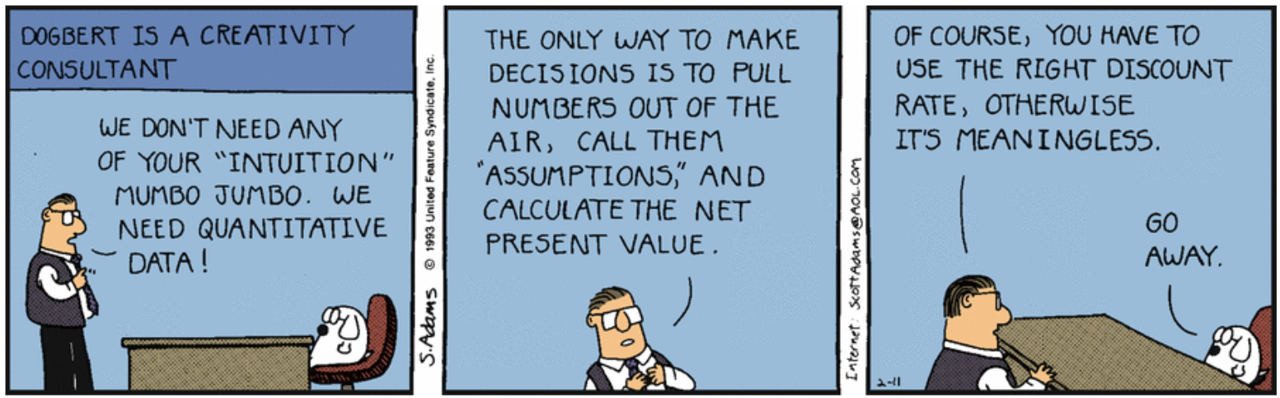

NPV depends on determining a cost of capital discount rate (Figure 1.1) reflecting the risk characteristics of the project. Finance offers CAPM, FF3F, APT, and other methods for this purpose. A basic NPV analysis assumes all equity financing, and Brealey and Myers (1981) recommends a separate analysis to determine the NPV of alternative financing.

Brealey and Myers (1981) offers, and quickly rejects, four alternatives to NPV

- Internal rate of return (IRR),

- Payback period,

- Discounted payback period, and

- Return on average book value.

The internal rate of return (IRR) is often considered a competitor to NPV. Applied carefully, IRR produces the same answer as NPV, but it suffers from some subtleties that make its application delicate. We focus on NPV, knowing that it also has an IRR flavor.

1.4.2 Insurance NPV analysis

How does an NPV analysis of the opportunity to invest in writing a short-duration insurance policy differ from the textbook ideal? This section describes five important ways.

The first involves the valuation paradigm. Classical finance assumes an efficient market with an additive pricing functional. Insurance, in contrast, relies on economies from risk pooling that exist because valuation is sub-additive, not additive. Compensation for diversifiable risk is better thought of addressing ambiguity aversion than risk. As a result, the cost of a policy to an insurer depends on the other business it writes.

In a textbook application costs are known when the product is sold whereas in insurance they are not, being determined by the random occurrence of future losses. Risk in the textbook model is on the revenue side, which is known for guaranteed cost insurance business. The textbook and insurer applications both have an uncertain total outcome, but the uncertainty is more endemic for insurers giving a second difference.

Related to cost uncertainty, insurers find it hard to quantify their capital investment at project inception, the third difference. Capital costs are pooled costs that need to be allocated to each unit. Cost allocation is often done by first allocating capital and then assuming all capital has the same cost, which the debt credit curve shows is not the case. Since different units consume capital differently across the capital tower, it is not correct to allocate capital and apply an average cost: cost and amount are correlated. Moreover, insurers have access to a unique form of financing called reinsurance in addition to debt and equity.

The fourth is related to regulation. Insurance is often mandatory and is typically purchased to protect a third party. In order for mandatory insurance to be effective, it must be provided by an adequately capitalized insurer. As a result, insurer solvency is regulated through minimum capital standards in almost all countries. Imposing a minimum capital standard results in an economic cost of the capital cushion because of the regulator’s right to takeover a company even when it has a positive net worth. Insurers may also be required to post capital sooner or hold it longer (“trapped capital”) than it is economically justified, because the owner’s interests may not be aligned with claimant’s. They may also face restrictions on the use of debt. Each jurisdiction manages solvency differently, and a multinational insurer must retain an adequate capital cushion in each legal entity it uses to write business. Rating agencies act as de facto regulators in some parts of the world, adding a further complication. As part of project evaluation, the resulting additional capital costs must be estimated and accounted for correctly.

The fifth and final deviation relates to accounting. As well as regulatory (statutory) accounting rules, insurers are subject to reporting, tax, and management accounting rules, and these can drive substantially different views of the underlying economics. For example, loss reserves are undiscounted in US GAAP, discounted for US tax, and discounted with a risk adjustment under IFRS 17. Again, passing multiple tests can result in additional costs.

In summary, we have identified five ways that insurance confounds application of textbook NPV methods:

- Value is not additive for diversifiable risk and costs depend on the portfolio within which a risk is written.

- Costs are not known when the project is sold, resulting in multi-period cost risk as liabilities emerge.

- The cost of the capital investment is hard to quantify and depends on the capital structure. Moreover, reinsurance is available as an additional source of financing unique to insurance.

- Capital is regulated and subject to minimums greater than zero, making it costly to satisfy minimum capital requirements.

- Insurers are subject to multiple accounting standards, each with different treatments of the same economic reality. There is a cost to “passing multiple tests”.

There are two further ways that insurance is complicated, particularly for US actuaries. The first is rate regulation. Rate regulation has spawned an arcane language and set of ad hoc methods. US actuaries must know how regulators expect profit provisions to be computed and adhere to additional standards in their work. This Monograph does not explicitly describe particular regulatory standards, but it does discuss the underlying principles. Actuaries tasked with rate filing work should consult their local rules and regulations for guidance. The second way, also aflicting US actuaries, is the split of income into underwriting and investment (or “banking profits”) components. The split was already contentious in the 1920s and 1930s. AMB quote. It is easy to suppose this separation has no economic effect; after all, it doesn’t affect cash flows. However, the combined ratio is incorporated into regulatory and rating agency evaluations, for example, US statutory IRIS ratio tests. Management is forced to monitor the combined ratio and may undertake economically costly activities to manage it. Again, this Monograph does not explicitly address this issue, but it does discuss the underlying principles.

Table 1.1 summarizes the adjustments needed to apply NPV to insurance, and includes references to the sections where these adjustments are discussed.

| Issue | Adjustment | Section(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Non-additive valuation | Price risk within a portfolio; \(\kappa\) pricing and understanding diversification | TODO REFS! |

| 2. Loss emergence | Develop a multi-year model of loss emergence and decompose risk; “independent sum” of emergence model | TODO REFS! |

| 3. Capital cost and structure | Relation between market pricing distortion and implied capital structure; importance of top and bottom layers; impact of debt limits | TODO REFS! |

| 4. Regulatory drag | Estimate the cost of regulatory capital requirements | TODO REFS! |

| 5. Multiple accounting standards | Estimate the cost of accounting differences; “greatest of” computation | TODO REFS! |